David Bowie is one of those rare artists who have helped define a decade. That decade was the 1970s – an era when world economies were sent into a spin by an oil crisis, and fashion went AWOL. Those were the years that saw the downfall of Richard Nixon, the rise of Margaret Thatcher, the death of Mao Zedong, and the sacking of the Whitlam government.

In his book, The Man Who Sold the World, Peter Doggett writes: “Perhaps because the sixties had felt like an era of progress, the seventies was a time of stasis, of dead ends and power failures, of reckless hedonism and sharp reprisals. The words that haunted the culture were decline, depression, despair…”

Was it really that bad? One could argue for the seventies as a continuation rather than a betrayal of sixties’ aspirations. It was the heyday of the Women’s Movement and a time of growing environmental awareness. In popular music we saw glam rock, heavy metal, disco, and other tendencies, until the Punk revolution arrived like a purgative.

Throughout it all, David Bowie produced one outstanding album after another, each accompanied by a new look, indeed, a new persona. From Space Oddity, which came out in November 1969, to Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), in September 1980, Bowie’s creativity was prodigious. This sequence of 13 studio albums must be one of the hottest streaks in rock ‘n’ roll history.

After 1980 it was never the same. Three years would pass before the next album, Let’s Dance (1983), and despite occasional revivals, Bowie’s star has waned. There’s a distinct tailing off in his music of the past two decades, although it compares favourably with the efforts of many fashionable performers who have followed in his wake.

If Bowie (b.1947) has found his seventies self an impossible act to follow it’s partly because the culture has changed. He once had the ability to shock and astound his audiences, but the globally wired world of today is virtually unshockable. Besides, does any artist still feel the need to astonish the bourgeoisie when he’s almost 70?

As a teenager who dutifully bought all the Bowie albums as soon as they were released, I imagined David Bowie is, at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, as a nostalgia trip padded out with old costumes and memorabilia.

Well the costumes and memorabilia are present, but the show originally put together by London’s Victoria and Albert Museum in 2013, proved far more absorbing than anticipated. David Bowie is, is an immersive experience that plunges visitors into a constantly shifting soundscape, thanks to a headset that picks up different songs depending on one’s location in the gallery.

This approach was so successful it may be the start of a new trend, with every major pop star in line for a museum survey, complete with soundtrack. We’ve already had all the fashion designers so music is the next frontier.

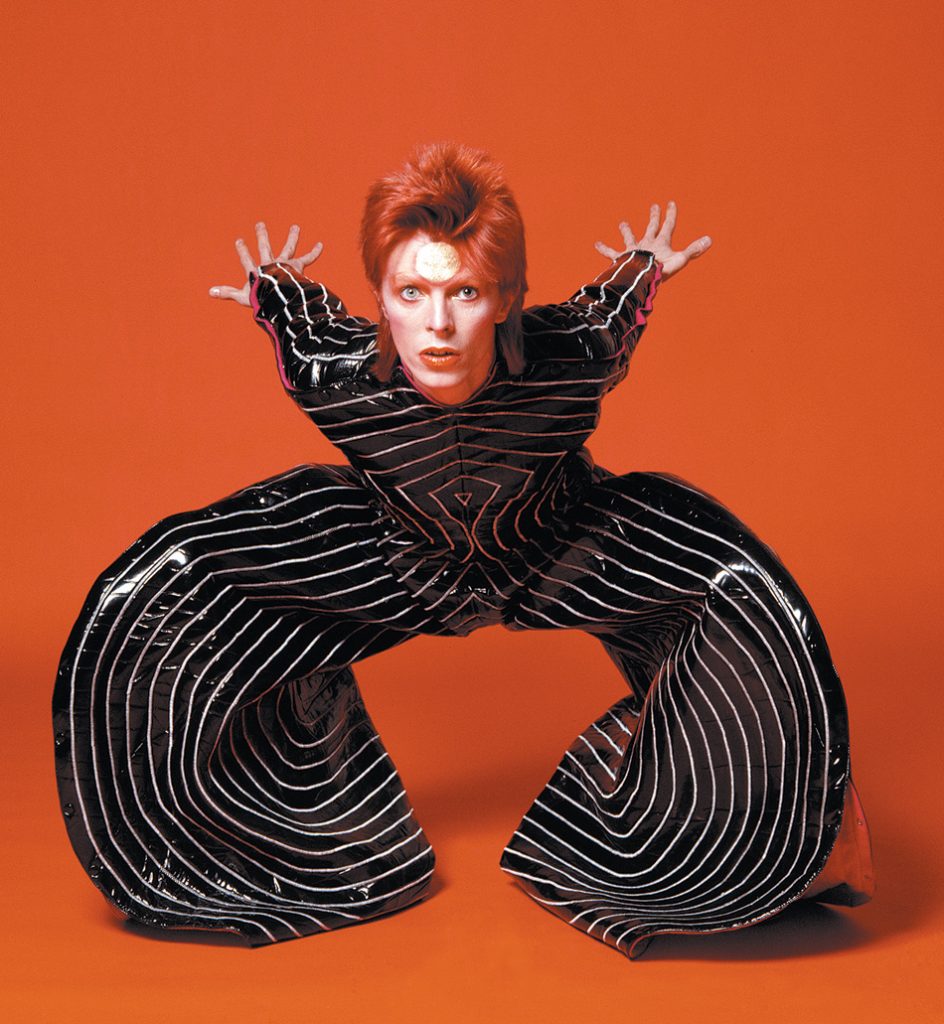

The stand-out items in this show are the costumes Bowie wore while playing roles, from the imaginary rock god, Ziggy Stardust, to the Pierrot of Ashes to Ashes. The best of the lot is the Tokyo Pop bodysuit designed by Kansai Yamamoto for the Aladdin Sane tour of 1973. A ludicrous slab of black vinyl, with grooves that echo those of a record, it puts Bowie literally within the music he is making. It’s hard to know how one would dress like an mp3.

Few of the other pieces can compete, partly because costumes on mannequins have none of the impact they enjoyed when worn on stage. Neither is there anything wildly exciting about old record covers, family photos, posters and hand-written lyrics. Pieces that provide an art context such as the old footage of Gilbert and George singing Underneath the Arches, are diverting, albeit familiar.

The real fascination is this exhibition lies in contemplating the phenomenon of David Bowie – rock chameleon, cultural bowerbird, showman, androgyne, bisexual, a connoisseur of his own contradictions, a mystery unto himself.

The catalogue is the essential guide: a whopping 320 page volume with an excellent set of essays, (including one by cult intellectual, Camille Paglia), that explore Bowie’s career from every angle. This book makes a persuasive case for the serious study of popular culture, as it tracks its subject’s roots in literature, cabaret, theatre, modern art, Hollywood and avant-garde film, social and political history.

To simply list Bowie’s preoccupations is to make him sound like a polymath, but he has approached every topic in the manner of a visual artist – registering significant elements, borrowing what is relevant to his own needs. His explorations rarely go far beneath the surface, but they are given a greater force when linked to his lifelong exploration of the self.

Bowie began life as Davy Jones, a lad from the working club London suburb of Brixton. He was introduced to the music scene by an older half-brother, Terry, who would suffer from schizophrenia, the family “curse” that has always haunted Bowie. His response has been to plunge into the most extreme situations, using music as a form of catharsis. He was cheerfully tempting fate when he dreamt up the character, Aladdin Sane.

The music found on his debut album, David Bowie (1967), is an unconvincing mishmash of styles, including the embarrassing novelty song, The Laughing Gnome. In those days Bowie just wanted to be noticed.

Everything changed when he recorded the single, Space Oddity in 1969. Not only did he come up with an original sound, but he tapped directly into a Zeitgeist obsessed with the conquest of space. Bowie’s astronaut, Major Tom, was no hero but the kind of disenchanted protagonist one might find in an Albert Camus novel. Major Tom was steeped in gloom as he contemplated the planet he had left – Planet Earth is blue and there’s nothing I can do.

This cynicism captured the mood of a new decade in which it was becoming apparent that the glorious hopes of the hippy generation were not going to be met. The world was ruled by businessmen, dictators and politicians, not Pop visionaries.

Bowie’s political views seemed inseparable from his ever-changing sense of personal style. He played the drag queen, the aristocrat, and even flirted with fascist chic. Along the way he re-defined every genre he touched – from the primal glam rock of Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane to the disco and soul of Station to Station and Young Americans. In Berlin, he shared a flat with Iggy Pop and came up with a dark, atmospheric sound that produced two classic albums for each party: Bowie’s Low and Heroes, and Iggy’s The Idiot and Lust for Life.

The song, Ashes to Ashes has been seen as a summa and testament of Bowie’s career. In the video clip, Major Tom returned as a character, as did a Pierrot that harked back to an early association with Lindsay Kemp. Even Bowie’s mother was there, walking along the beach, remonstrating with her wayward son.

This clip occupies a pivotal point in the show, although it is only the beginning of the self-reflections that recur throughout Bowie’s later work, right down to the cover of his latest album, The Next Day, which reprises the photo from the Heroes LP. From a wall of more recent videos, clips such as Blue Jean and The Stars (Are Out Tonight) resemble small pieces of cinema rather than vehicles to sell a song.

For all of his achievements, which belong not only to the realm of rock music, but to art and performance art, Bowie is a strangely incomplete figure. As a singer he relies heavily on vocal mannerisms. He is not in the same galaxy as a vocalist such as Freddy Mercury. His limitations are most exposed with cover versions, which almost always sound affected. The interest lies in the choice of the song, not the delivery. God only knows why he ever chose to mangle the Beach Boys’ God Only Knows.

With his own material it’s usually a different matter, as the song feels inseparable from the voice. Each piece fits into the puzzle of Bowie’s changing identities. He is rock music’s Man of a Thousand Faces, forever picking up the fragments of discarded selves, leaving us wondering what’s left behind the mask.

David Bowie is

Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne, Until 1 November

Published in the Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 12th September, 2015