When an artist calls a work A Painted Picture of the Universe it means he’s thinking big. It’s rather a grand title for a small abstraction, even if it did take Roy De Maistre 14 years to complete this cosmological fantasy.

De Maistre (1894-1968) is one of the central figures in Sydney Moderns: Art for New World at the Art Gallery of NSW. He is present at the beginning of the show with some of the earliest abstractions painted in Australia, and there at the end, after having moved to London where he became a mentor to the young Francis Bacon.

De Maistre was born as Leroy Livingstone de Mestre, to a family of thoroughbred racehorse breeders in Bowral. He would exhibit under a range of Frenchified variations on his original name, showing a taste for theatricality and self-fashioning typical of the period explored in this exhibition. First came the wild release of tension at the end of World War One, then the increasing gloom of the 1930s, as the Great Depression began to bite. They were febrile, nervous unsettled times – an atmosphere that always seems to produce good art.

If you’re still reeling from the monstrous indulgence of Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby, Sydney Moderns may provide the antidote. It doesn’t tell a story of decadence and excess, it shows how artists entertained the highest ideals with the slenderest of means. Unlike the gargantuan canvases being made today to sell to museums, the pictures in this show are easel-scaled and smaller. The sculptures are equally modest in their proportions. There was only a tiny audience for Modernist art in Sydney in those days, although it was a different story for design, fashion and Art Deco architecture.

The bulk of this exhibition is drawn from the holdings of the Art Gallery of NSW, but it is fascinating to see these works in a new context, juxtaposed with astute borrowings from public and private collections. There’s no disguising the fact that this year’s exhibition program at the AGNSW is lean, but Sydney Moderns is an unexpected highlight. Curators, Deborah Edwards and Denise Mimmocchi, have put together a show that has been well planned and exhaustively researched. There is an excellent catalogue, and one can appreciate the care taken in the arrangement of works and choice of wall colours.

The concern for detail extends to the shop, which features a range of specially commissioned products by local manufacturers drawing on the colours and styles of the 1920s and 30s. The idea of making these items seems to have begun with the reconstruction of a room designed by Hera Roberts, for a 1929 exhibition at Burdekin House. Having made facsimile furniture and fabrics for this installation, it was an obvious next step to produce extra material for retail. It’s a bold gesture that deserves to succeed, if only to prove that exhibition shops need not be stocked exclusively with tatty souvenirs.

Sydney Moderns is no blockbuster, and is not swathed in the same egregious hype that accompanies so many large-scale touring shows. Instead, it does what an historical survey should do: taking a close look at the art of a period, dispelling myths and misconceptions, examining the achievements of the major figures, and uncovering works by neglected artists, including those who stayed only briefly in Australia, such as Frank Weitzel and Niels Gren.

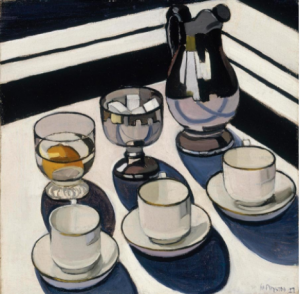

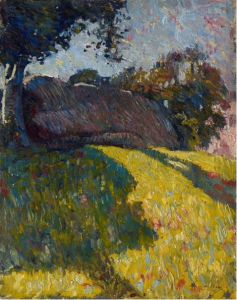

This survey is bookended by works from two seminal exhibitions: De Maistre and Roland Wakelin’s Colour in Art of 1919, and Ralph Balson’s solo show of 1941, the first in Australia devoted to purely abstract paintings. In between there are sections on landscape, still life and modern design, revealing the wide range of influences at play in the Sydney art scene, and the many different interpretations of what it meant to be modern.

It was a scene distinguished by impurity and eclecticism, where artists argued about whether one might abstract a composition from a subject or dispense with the subject altogether. Some sought for underlying laws and rules, some embraced the spiritual values of Theosophy and Anthroposophy. Others simply followed fashion. This was not as superficial as it sounds because the links between art and design were much stronger in the 1920s-30s. In a catalogue essay, Terence Maloon looks at the importance of the word “design” for the influential British critic, Roger Fry. In other essays, it is frequently mentioned how artists used the term “decoration” in a positive, not a pejorative sense.

Most people in Sydney may have seen Modernism as a decadent activity undertaken by foreigners, but the movement never had revolutionary ambitions. We habitually invest the past with a false glamour and intrigue. The truth is that everyday life grows much more exciting in retrospect, when all the dull bits have fallen away, leaving dazzling anecdotes and larger-than-life characters. This process of Hollywoodisation is reinforced by those who partook of the actual events but have allowed their memories to settle into more appealing forms.

The received idea is that Modernist art was always greeted with rancorous hostility from the critics and the art establishment. The truth is that avant-garde and academic artists tended to ignore each other rather than engage in warfare. Although there were a few diehard reactionaries amongst the critics, notably Howard Ashton, much homegrown modern art was reviewed with interest and sympathy. It’s only to be expected that most private collectors had conventional tastes, but there was a significant minority attracted to the colour and dynamism of the new art.

Neither should we assume that avant-garde artists went out of their way to shock and offend. On the contrary, they took pains to explain and justify their work by means of articles and lectures. De Maistre and Wakelin felt obliged to introduce their Colour in Art show with brief talks. As a writer, Margaret Preston was tireless in her efforts to popularize modern design and handicrafts, not to mention her grand vision of a national art based on Aboriginal colours and motifs.

In those days before the avant-garde was subsidised by public money, artists could not afford to alienate potential clients. Some, such as the stylish Adrian Feint, adopted a kind of ‘juste milieu’ approach, adding a touch of Surrealism to immaculately finished flower paintings based on Dutch old masters. Feint saw no contradiction in being both Modernist and blatantly commercial. His peers may have envied his popularity, but they never railed against his methods.

One could hardly accuse the influential publisher, Sydney Ure Smith, of being a rebel. Through titles such as Art in Australia and The Home, Ure Smith promoted a broad spectrum of art, and kept up his tries to high society. He also provided employment for artists at the advertising agency, Smith and Julius. Those in Ure Smith’s ‘gang’, such as Feint, Thea Proctor, Hera Roberts and that brilliant photographer, Harold Cazneaux, received the benefits of constant exposure and publicity.

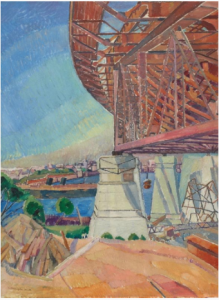

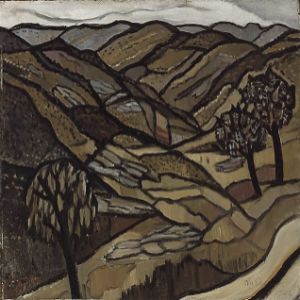

None of this easy celebrity was bestowed on Grace Cossington Smith (1892-1984), who was marginal to the Sydney art scene, but now looks like one of its most original talents. The extraordinary range of Cossington Smith’s work is well represented in Sydney Moderns, from her dark, brooding crowd scenes and cityscapes of the early 1920s, to heroic vistas of the Harbour Bridge under construction, and small, visionary pictures such as Black Mountain (1931), which have no precedent in Australian art.

The show ends with Ralph Balson (1890-1964), who continues to make his way up the ranks of Australian artists, outstripping his peers such as Grace Crowley, Rah Fizelle and Frank Hinder. Making Balson the subject of the last room is to portray him, perhaps accidentally, as the culmination of the period. Yet this is a retrospective perception based on the abstract tendencies of the next wave of local avant-gardists, for whom Balson acts as precursor.

Balson, in his way, is as singular as Cossington Smith. Even though his work grows out of Cubism, it moves in idiosyncratic directions. By the early years of the Second World War, when this survey concludes, he was still full of the joys of geometry. In later years he would adopt an increasingly informal, gestural approach.

One painting that is not in the show, but would have been a perfect addition, is Herbert Badham’s Travellers (1933), recently sold for a record price at Bonham’s auction of items from the Grundy Collection. Basically a genre scene showing people sitting on a tram, it contrasts the dull-coloured clothes of the men with the dazzling hats worn by two women, throwing a sudden splash of modernist design into the most commonplace observation. It is a wry acknowledgement of Modernism’s stealthy advance within the framework of a realist painting.

Another notable omission is Charles Meere’s Australian Beach Pattern (1940), which the AGNSW has generously loaned to the survey of Australian art being held at the Royal Academy in London in September. The AGNSW should be praised for this unselfish act, so uncharacteristic of Australian public galleries, but this iconic work might have been better situated in this well-focused survey rather than the encyclopaedic spread of the London show. The big showcase may have its appeal, but as Roy De Maistre demonstrated, one may reside in the provinces and still manage to capture the universe on a small piece of board.

Sydney Moderns: Art for a New World, Art Gallery of NSW, July 6 – October 7, 2013.

Published in the Sydney Morning Herald, July 20, 2013.