South of no North may seem an enigmatic title for an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, but a moment’s reflection provides clarity. The name of this show, which brings together the work of Laurence Aberhart, William Eggleston and Noel McKenna, is borrowed from a book of short stories by Charles Bukowski (1916-1994). This infamous beatnik was the foremost American exponent of that vein of literature the French called nostalgie de la boue. For a translation of this phrase it would be hard to improve on Merriam-Webster: “yearning for the mud: attraction to what is unworthy, crude or degrading.”

Aberhart is a celebrated photographer from New Zealand, William Eggleston hails from Memphis, Tennessee; and McKenna was born in Brisbane, but has spent most of his life in Sydney. Although the differences between these artists probably outweigh the similarities, in world terms they are all southerners.

The geographical distinction is less important than the cultural baggage that comes with the term. In Europe the frozen north is associated with qualities such as intellect and order, while the sunny south is traditionally viewed as anarchic and sensual. The north is rational and Protestant, while the south is superstitious and Catholic. The north puts a greater emphasis on the mind, the south on the body, and so on.

There is nothing scientific in this bundle of prejudices, but it is close enough to the truth to ensure its longevity. The current economic meltdown in countries such as Greece, Spain and Italy, provides further fuel for the old north-south dichotomy.

While northerners may enjoy a sense of superiority over their southern peers, they are also envious of the easier, more physical life they associate with these countries. Goethe’s Italian Journey (1816-17) is probably the most famous literary statement of this sentiment. He admired both the lifestyle of Italy and the classical remnants of the Roman era.

In the chasm that separates the high-minded Goethe from Bukowski, the self-confessed sleazebag, we can catch a glimpse of the thinking behind this exhibition. The sensuality of the south is only defined in respect to the uptightness of the north. Take away that reference point and the south takes on a different aspect. The ‘southern’ perspective of Aberhart, Eggleston and McKenna produces works that are neither sensuous nor classical. On the contrary, there is a melancholy, a pervasive irony in their choice of subjects.

This show is part of an occasional series in which the MCA invites an Australian artist to select an overseas peer with whom they would like to share an exhibition. Noel McKenna (b.1956), a painter of deadpan, quasi-naïve pictures, took an unorthodox approach by suggesting two photographers. Laurence Aberhart (b.1949) is known for his use of an antiquated, large-format camera that brings a stillness and monumentality to images of everyday life he has taken in New Zealand, Australia, the United States and France.

William Eggleston (b.1939) is one of the world’s most influential living photographers, known for his bold use of colour and the offbeat nature of his imagery. In 1976 Eggleston was the subject of only the second show of colour photography held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, fourteen years after a survey by Ernst Haas. For some reason Haas is often forgotten and Eggleston credited as the one who made this historic breakthrough.

This is probably because Haas was a classical stylist while Eggleston not only offended against the conventions of black-and-white art photography, he threw out any notions of good taste. That 1976 show, Guide, generated enormous hostility. When curator, John Szarkowski declared Eggleston’s photos to be “perfect”, critic Hilton Kramer, responded they were “perfectly banal” and “perfectly boring”.

Had he been able to see where Eggleston’s example would lead, Kramer would not have repented; he would have declared our entire civilization is now infected with the taste for banality. In a sense it’s true – the new photography by Germans such as Andreas Gursky, Wolfgang Tillmans and Juergen Teller, makes a virtue out of banality. Eggleston is also seen as a major influence on filmmakers such as David Lynch and Gus Van Sant, who turn the everyday into something strange and disturbing.

Perhaps this is Eggleston’s great contribution to the visual arts – the discovery that by concentrating on the most banal scenes; by isolating them and re-presenting them in unnaturally vivid colours, one can imbue them with a sense of mystery. Eggleston is not the first to do this, but he has done it with a depth and consistency that deserves to be called a vision rather than a strategy.

Take for example his well-known photo of a pink light bulb set in the red ceiling of a red room, skewered by three white power cords. This nondescript scene is given an infernal dimension by the ferocity of the colour. When Eggleston photographs bags of rubbish or the items crammed into a freezer, we find ourselves staring at these pictures as if they depict great works of sculpture. A man sits on a bed, lost in thought. But what is he thinking?

Curator, Glenn Barkley, describes the work of Eggleston and the other two artists as “akin to short stories”. Presumably he means those stories in which an epiphany creates a moment of revelation, a hole in the fabric of domestic reality. It’s there if you want it, but the viewer who hopes to be floored by some astonishing image or a display of superior skill, will be disappointed.

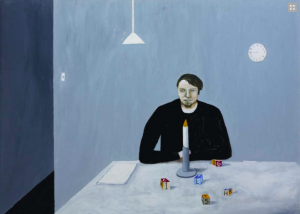

One can see why Noel McKenna admires Eggleston, as his own style of painting is so radically deskilled. McKenna is that strange phenomenon of a highly professional artist who paints like an amateur. His subjects are the built environment, mainly houses and rooms. He paints dogs and cats, and those ‘roadside attractions’ such as the Big Pineapple or the Big Orange that celebrate Australia’s local produce. When McKenna paints people they resemble cartoon figures or children’s drawings. His actual painting often seems to be no more than a form of colouring-in.

And yet, these seemingly amateurish pictures have a canniness that belies first impressions. In the stringent geometry of his compositions, his colour choices and subjects, McKenna reveals himself as a thinker. His pictures always feel like fragments of a narrative, perhaps not far removed from our own experience. His suburban houses and rooms are like thousands of houses and rooms we have encountered. His picture of the Big Pineapple at Gympie can’t be very different from any tourist snapshot. In fact it’s probably based on a snapshot, as this vernacular icon was torn down years ago, leaving Nambour as Pineapple Central.

Eventually one comes to appreciate McKenna’s habit of not trying too hard to create a realistic impression. He gives us all the information we need to set our imaginations in motion. His pictures are not windows onto the world, but diagrams. They might describe a way of life or a state of mind, but we need not search for any moral program. When McKenna’s work has occasionally drifted in the direction of satire and social criticism it has been much less effective. He is at his best when he documents the blank absurdity of life in a way that makes it seem homely and comfortable.

Laurence Aberhart differs from his co-exhibitors in his willingness to embrace a more overt form of humour. Many of Aberhart’s photos are visual gags, and none the worse for that. His picture called Faith Tabernacle, Port Gibson, Mississippi (1988), shows a pathetic little shed, an unkempt field of grass, and a sign that boldly proclaims: “Prayer Works – Try It”. His image of Vicksburg, Mississippi, with an arrow pointing us in the direction of Dykes Furniture Centre is just as funny. As is a tiny, isolated hovel that promises to enlarge your photos; and a four-square, perfectly symmetrical snap of the King Konkrete factory, in Waitara, Taranaki.

Other pictures, such as his photos of cemeteries and portraits of his children, have an intrinsic sadness, as if he is meditating on mortality and the fleeting nature of childhood. One truly amazing image called Domestic architecture: Ipswich, shows a house so barricaded, so flattened and oblique it makes McKenna’s views of grey suburbia look like fun-parks.

If Aberhart seems less detached from his subjects than Eggleston and McKenna, the show has been selected and arranged intelligently to bring out contrasts and points of convergence. Works have been hung in thematic clusters so we can see the way each artist takes on motifs such as buildings, interiors, children and popular culture. The juxtapositions invite us to read each image in relation to the next, so the overall experience is greater than the sum of its parts.

Were the show arranged so each artist had a section to himself we might be less sympathetic to many of these images. The photography critic, A.D.Coleman, once described the work of Eggleston, Gary Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, as “self-consciously aestheticized glimpses of the incidental aspiring to the status of the eventful”. The curatorial art consists of making us believe that what is incidental may actually be crucial.

South of no North: Laurence Aberhart, William Eggleston, Noel McKenna

Museum of Contemporary Art, March 8 – May 5, 2013

Published in the Sydney Morning Herald, April 6, 2013