It’s distressing that every time I’ve written about Newcastle this year the exhibition has had to share column space with some new crisis. The only progress is that these crises keep getting worse, with the latest developments being almost unbelievable.

At a meeting on 24 September, the Council voted to adopt a controversial restructure proposed by general manager, Ken Gouldthorp, that will abolish the position of director of the Newcastle Art Gallery and install a “Cultural Facilities Manager” who will take charge of the gallery, the Newcastle Museum and possibly the Civic Theatre.

This is the kind of drastic measure normally brought about by catastrophic mismanagement or financial meltdown. Yet Newcastle, by common agreement, is one of the best managed galleries in the country. It has an excellent director in Ron Ramsey, who has brought in a succession of valuable bequests and donations, the latest being an $850,000 Brett Whiteley sculpture, gifted by the artist’s widow, Wendy. The gallery also has a strong group of friends and supporters who have raised the $40,000 required to bring the sculpture to Newcastle.

Newcastle’s property developer mayor, Jeff McCloy, has already distinguished himself by suggesting the galley raise money by selling the works in its permanent collection. He suggested at the time that the gallery should pay for the renovation by selling off works in the collection. Apparently the Council can’t afford to pay for a long overdue renovation, although it has millions to spend on a rearrangement of Laman Street in front of the gallery, which has been going on for months. There are also funds for the beautification of Hunter Street, which may benefit properties and businesses on that unlovely thoroughfare, but shouldn’t take priority over the gallery, which is a facility to be enjoyed by every citizen and every tourist.

The proposal to abolish the position of director was narrowly approved at a confidential session of the council. Councillors opposed to the changes said they weren’t given sufficient time to review the plan, copies of which were returned to the council at the end of the meeting to prevent its leaking. The restructure is an act of consummate brutality that will take one of the leading regional galleries in the country and turn it into a major embarrassment.

Many directors treated in this manner would be ready to man the barricades but Ron Ramsey has met this humiliating scenario with extraordinary courtesy and discretion. He will get another job, and Newcastle will lose a popular and highly effective director. One expects that bequests and donations will drop to zero, while exhibitions will be dealt with in perfunctory fashion. Supporters of the Newcastle Art Gallery are waiting nervously to see whether the plan to sell off works from the collection is reinstated.

A gallery on the scale of Newcastle with no director is not so very different to a large vessel without a captain, or perhaps a city without a mayor. The friends of the gallery will have experienced a touch of Schadenfreude when they heard that Mayor McCloy’s $15 million luxury yacht caught fire and sank off the Daintree coast earlier this month.

Those who wish to visit the Newcastle Art Gallery before it disappears beneath the waves will be impressed by the exhibition, After Five: Fashion From the Darnell Collection. This show was originally put together for the Hazelhurst Regional Gallery earlier this year, and has been slightly reworked for the Newcastle season. As usual a great deal of thought has been put into the hang, which has been one of the features of Ron Ramsey’s directorship.

It’s a pleasure to sample the subtleties of this arrangement, especially as I’m still trying to exorcise memories of the chaotic, amateurish hang of Australian art at the Royal Academy, London. Over the past couple of decades, museums around the world have discovered the pulling power of fashion. The trend began with Diana Vreeland, who worked as a consultant to the costume department of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in the 1970s, but by now almost all the major couturiers have enjoyed prestigious retrospectives. Readers may recall the Valentino survey at the Queensland Art Gallery in 2010 and Vivienne Westwood at the National Gallery of Australia in 2004.

The Darnell Collection is a different proposition, being based on the private holdings of the late Doris Darnell, a Philadelphian Quaker, with an unorthodox passion for clothes. In 2004, Darnell bequeathed 3,500 items to her Australian-based goddaughter, Charlotte Smith, who has continued to acquire pieces through purchase or donation. There are now more than 8,000 items in the collection, which has become one of the world’s great private repositories of fashion history.

For many years the collection kept Smith on the brink of poverty, but now she is beginning to realise the value of this resource, with numerous exhibitions planned for Australian and international venues. She is a great ambassador who is willing to write and lecture about the collection, and even model the clothes. This kind of infectious enthusiasm may only be possible with a curator who has such a direct stake in a project. For Smith, the Darnell Collection is not merely a hobby – it’s her life and livelihood.

I’m not going to use this column to provide a summary of modern fashion history, even if I were capable of such a feat. One of the principles of this collection is that every dress and accessory tells a story. There is the big picture of social history – the way that styles and choice of materials reflect the temper of the times, whether it be the feverish glamour of the 1920s-30s, the austerity of the war years, or the cultural diversity of the 1960s.

Other stories are private in nature: the stories of the women who owned these garments, and the occasions on which they were worn. It’s a safe bet the majority of these designer gowns saw little active service.

Another important aspect of the Darnell Collection is the way it combines the work of celebrated international designers such as Coco Chanel, Christian Dior, Mary Quant and Yves Saint-Laurent, with those of lesser-known Australian couturiers such as Christopher Essex and Michelle Jank. In parallel with the visual arts, such juxtapositions allow viewers to judge the degree to which Australians have been influenced by their overseas counterparts and where they have found an original voice.

One of the most touching pieces in this respect is Barbara Coty’s Graduation party dress (1951), made on the occasion of her leaving East Sydney Tech, (AKA. The National Art School). Coty had already felt the influence of Dior’s New Look in her home-town of Canowindra, before a scholarship brought her to study in Sydney. Unable to find a suitable fabric she silk-screened black polka dots onto white organdie to create a dress that looks amazingly fresh, even today.

Dior’s New Look holds a legendary position in fashion history because it came along at the end of World War Two, announcing to the women of the world that it was once again acceptable to look elegant and glamorous. Nancy Mitford, herself a devotee of the New Look, said the effect was like “a magic potion”. The impression was magnificent, so long as a woman didn’t attempt to walk or sit down.

A cocktail ensemble by Dior, dating from 1948, shows that characteristic mixture of crisp lines and artful construction. Although this dress and jacket look simple, they are filled with padding and boning, giving an almost sculptural dimension to the outfit – and by extension, to the wearer.

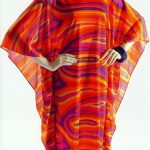

For every moment in fashion when dresses become over-elaborate or constrictive, there is a counter-movement that allows a greater sense of freedom. The ultimate example being perhaps the kaftans of the 1970s, represented here by a particularly lurid example by the Australian designer, Ninette. But soon those chic, barely wearable designs come rushing back. It is a constant reminder that haute couture is not made for comfort, but for projecting an image. Evening wear, the ostensible subject of this show, is a world away from the everyday round of work and domestic life.

The After Five look was made for standing around sipping cocktails, not for dancing the night away. It is an assumed attitude – an expression of wealth and power, both financial and sexual. These are dresses that turn their wearers into living works of art, as alluring and untouchable as statues in a museum.

Published in the Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 26th October, 2013