“I have tried too in my time to be a philosopher,” said Dr. Johnson to his biographer, Boswell, “but I don’t know how, cheerfulness was always breaking in.”

Seeing the exhibition, Lampoon: An Art Historical Trajectory 1970-2010, I thought these lines were oddly appropriate for Jim Anderson. In a retrospective at Sydney University’s Tin Sheds Gallery he covers most of the great political and spiritual issues of the past four decades in works of consummate frivolity. But despite an impressive record of dropping out, freaking out, taking bad trips, and becoming immersed in alternative lifestyles and therapies, Anderson (b. 1937) still manages to come across as a sane and rational human being.

His secret has been a sense of humour and an innate skepticism that kept bringing him back from the brink of one hippie excess after another. During a festival in San Francisco, he writes: “I got a dismissive bang on the head from the Karmapa, the Tibetan lama (whose sixth sense detected cynicism).” One need not be a Tibetan lama to achieve such insight.

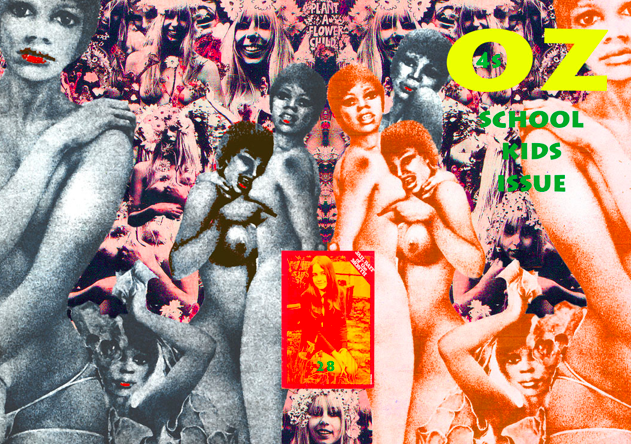

Lest we forget, Anderson was the third man in the infamous Oz magazine obscenity trial of 1971. Together with Richard Neville and Felix Dennis, he was hauled into the Old Bailey and interrogated by the dashing Brian Leary QC, about his attempts to “corrupt the morals of children and other young persons within the Realm… and to implant in their minds lustful and perverted desires.” These are the kind of talents that should ensure someone a job with a major advertising agency, but unfortunately the Oz editors were dedicated anti-establishmentarians, and viewed as a potential threat to law and order.

It is history that the obscenity charges were (eventually) thrown out, but this was also the beginning of the end for the magazine, having achieved a crescendo that made everything else seem anti-climactic. As Anderson puts it: “The trial had united the disparate elements of the counter-culture for a short time, but it also sucked all the air out of Oz.”

The youthful revolutionaries went on to find their niches within the capitalist system. Felix Dennis has become a wealthy publisher and poet; Richard Neville a self-styled “futurologist”, available for corporate functions. Among the Australian editors, Richard Walsh went on to be Managing Director of Australian Consolidated Press.

It is only Jim Anderson and Martin Sharp who have apparently attained life membership of Bohemia. Sharp, celebrated last year by a survey at the Museum of Sydney, lives like an urban hermit in Bellevue Hill. Now it is Anderson’s turn for closer look. If he remains the least known of the group it is partly because he spent about eighteen years in the small town of Bolinas in northern California, a counter-cultural Mecca that should not be compared to Nimbin. Back in Sydney from 1993 he has continued to take photographs, make satirical collages, and play an active role in the multifarious cultural activities of the Gay community.

Lampoon traces the peripatetic career of an occasional artist. For a detailed portrait of the counter-culture, one must turn to Richard Neville’s books, Playpower (1970) and Hippie Hippie Shake (1995), but Anderson has written a brief, lively memoir for the catalogue of this show that captures the flavor of those days with a kind of wry detachment. Indeed, he writes about his own life as if he were a spectator, not the leading protagonist.

There are no masterpieces in this exhibition, which consists of designs for magazine covers and posters, photographs and documentation. It is a great sprawling anthology of borrowed images and styles, often at the service of some exercise in political consciousness-raising. This encyclopaedic display is held intact by Anderson’s wit and his sheer joy in uniting incongruous motifs in unlikely configurations.

As long-term editor of the Bolina Hearsay News, a weekly newsletter, Anderson was obliged to come up with an original cover image for every issue. Any artist that has been subject to such a discipline will probably admit the experience was an excellent way of refining and extending his or her abilities. The cover designs in this show explore a wide range of styles, from psychedelia to Mayan Indian, to Dada and Surrealism. While he was concocting these covers Anderson was also writing, working part-time in a local bar, making masks and undertaking ritualistic performances. He was constantly busy, but almost invisible outside of the small world of Bolinas.

Whenever a project began to assume an air of respectability, Anderson quickly lost interest. When he became Art Editor of Oz, with his own office, his zest for the work disappeared. It wasn’t exactly what the French call “nostalgie de la boue” – which describes a taste for the low life, but an irresistible attraction to the margins. As the mainstream grew increasingly repulsive during the Reagan years, the margins felt like a much happier place to put down roots. Implicit in this is the recognition that all the political posters, all the protests, the fundraisers and good causes, have little impact on the vast edifice of global power. For some people this provides a reason to give up and rejoin the rat race, but Anderson seems to have gained a sense of freedom from this thought. It was as though he was licensed to do anything he liked, knowing at heart that it was only a gesture, albeit a gesture made with passionate conviction. He was undeceived but never disenchanted.

This has led him to quite savage satires such as The belles of St. Mary’s (2003), which uses a Cartier-Bresson image to poke fun at Cardinal Pell and the attitude of the Catholic Church towards homosexuality. Anderson’s dig at architect, Harry Seidler, is only slightly more subtle, in an 2009 image that depicts the pylons of the Sydney Harbour Bridge transformed into four facsimiles of Blues Point Tower. Other works seem to have been generated by puns, such as VietNamatjira (2006), showing Australian diggers patrolling a Namatjira watercolour landscape; or a portrait of Ludwig Van Beetroothoven, composing his Vegetarian Symphony.

As an artist who has been out of the closet for about forty years, Anderson has numerous pieces that one might describe as ‘camp’ – a quality that translates as “fun” to some people, and “self-indulgent” to others. There is the usual quotient of male members one comes to expect from outspokenly Gay artists, but he doesn’t suffer from the arbitrary phallomania that afflicts some of his peers. In his best collages there is always a point, if you’ll pardon the expression.

Much the same could be said about Anderson’s co-exhibitor, Phillip Juster (1952-2004), another Gay artist whose interests defied the stereotypes. The curator of this show, Robert Lake, writes that Juster showed an early taste for politics, declaring himself a Maoist while still at Clontarf High School. Throughout his life he would have an abiding interest in the culture of China, India and South-East Asia, and later the Pacific Islands. This found its way into his paintings and collages through extensive appropriations.

Like Anderson, as his political convictions became less ferocious Juster adopted a more satirical, irreverent approach. In this, he claimed to be influenced by the Punk movement, Dada, and Andy Warhol, once memorably described as “the nothingness himself”. Although a completely blank personality, Warhol was arguably the most influential artist of the late twentieth century. Juster may also have been affected by his long-term partner, Peter Blazey (1939-97), a larger-than-life character who defied all categorisations. Their relationship broke down in the early 1990s. Before long both men would become casualties of the AIDS virus.

In this show we can only see Juster’s work as a series of fragments, but there is a verve and intelligence that testifies to a promising career cut short. Although he was drawn to political themes, Juster is more of an aesthete than Jim Anderson. He often seems less concerned with a message than with fine-tuning an image. He is more minimal in his approach, happy to leave out those parts of a picture that are not strictly essential. It would be a travesty to simply call this “Gay art”, for while it may be Mardi Gras time once again these exhibitions prove that within the usual hedonistic whirl there is room for more cultivated pleasures.

Published for The Sydney Morning Herald, February 26, 2011

Jim Anderson: Lampoon: An Art Historical Trajectory

Phillip Juster: Collage 1952-2004

Tin Sheds Gallery, until 12 March.