Dimitri Shostakovich was 22 years old and freshly out of the Leningrad Conservatory, when he wrote the opera, The Nose. The piece is based on Gogol’s famous short story of 1836, in which a minor civil servant wakes to find his nose missing from his face. The protagonist pursues the fugitive organ through the streets of St. Petersburg, but it has developed airs and graces, and refuses to have anything to do with him. Finally the nose is returned by a policeman, after having been arrested trying to board a coach while disguised as a gentleman.

If this is hard to visualise, how much more daunting to turn the story into an opera and put it on stage? Gogol’s story was a grotesque parable in its day, and it still admits of no definitive interpretation. The tale anticipated the Theatre of the Absurd, and the imagery of the Surrealists who abandoned everyday logic in favour of the unlimited possibilities found in dreams. For Shostakovich, composing at a time of revolutionary euphoria, the story was an open invitation to experiment. In the final score there are elements of American jazz, the Romantic harmonies of Tchaikovsky, and the stark discordancies of Alban Berg’s Wozzeck.

I confess to not yet having heard The Nose. It has never commanded a place in the repertoire of the world’s opera companies. In fact, it has hardly been seen at all since its first full performance in 1930. The piece was immediately denounced as formalist and put in mothballs, not to be restaged until 1974 in Moscow, and 2009 in the United States.

Four years ago, the versatile South African artist, William Kentridge (b. 1955), was invited to design and direct a production of The Nose for the Metropolitan Opera of New York. It was not Kentridge’s first venture into the medium, as he had already been responsible for highly original productions of The Magic Flute and Monteverdi’s The Return of Ulysses.

As befits a story about an obsession, the opera became Kentridge’s all-consuming preoccupation. The piece was performed in New York in March this year, and has since been restaged at a festival at Aix-en-Provence. Directors of Australian arts festivals please take note: The Nose would be a highly desirable item for any program, especially with a big exhibition of Kentridge’s work due to be shown next year in Melbourne, at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image.

Part of the staging of The Nose was reconfigured into an installation that Kentridge showed on Cockatoo Island during the 2008 Biennale of Sydney. He has also completed a suite of prints and a series of small sculptures. Some of these were shown at Annandale Galleries in 2008, but now one may see the entire set, along with the artist’s poster for the 2010 FIFA World Cup, and other works. This is accompanied by an exhibition of jewelry by Lisa Black, in the gallery’s front room, which echoes Kentridge’s taste for wry historical references.

Following Shostakovich’s lead, Kentridge has taken The Nose as a vehicle for free association. His prints borrow imagery from the Bolshevik revolution, drawing on historical photographs and the works of pioneering avant-gardists such as Tatlin and Malevich. He also plunders the French Impressionists’ back catalogue, adding the enormous black silhouette of a nose to pictures by Manet and Degas.

The variety of printing techniques, and the unpredictable juxtaposition of images make this a consistently engaging portfolio. It is not, however, a masterpiece of drawing or technical finesse. As a draughtsman Kentridge is almost willfully crude. He hacks and scratches at an image as if he is trying to vandalise it. He throws diverse motifs together in a way that seems more like a random collage than a composition. In the finished works this translates into a tremendous sense of freedom – a superabundance of ideas, visual gags and allusions. This is very much his usual manner of working, and it chimes in neatly with the wild invention found in Gogol and Shostakovich.

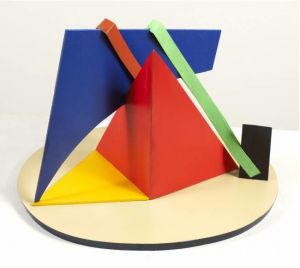

This brings me to a show by another distinguished overseas artist, Phillip King (b.1934), who is exhibiting monotypes and small sculptures with Defiance Gallery in their new Paddington venue. Here the invention is not so cerebral, the play of associations less rigorously signposted, but once again there is a powerful sense of creative freedom.

If we choose to ignore the burgeoning fame of younger artists such as Anish Kapoor and Antony Gormley, King is arguably Britain’s most celebrated sculptor after Anthony Caro. One could hardly put him in the same frame as the new generation sculptors, who have become known as makers of large-scale installations that require the collaboration of many assistants and technicians. King is happy to work on a small scale in a crowded studio that has the ambience of an average bloke’s shed. For today’s current crop of artist-capitalists nothing less than a factory will do.

Like Kevin Connor and Jeffrey Smart, recently reviewed in these pages, King is at a stage in his life when he doesn’t have to prove anything. Yet a glance back over his career reveals an artist who has never stopped taking risks, moving from figurative to abstract work, then back to a kind of “symbolic figuration”. He has been equally promiscuous with materials – working in steel, plaster, wood, plastic, fibreglass, paper, and any other substance that offered a new set of possibilities. He has a love of bold, clashing colours that seems almost an offence against sculptural etiquette, as the field is so often identified with monochromes and rust.

The small sculptures in this show are as vibrantly coloured as anything King has attempted, and make no pretence to tastefulness. They are shamelessly playful, but still manage to balance curves and angles, solid forms and flat shapes, in a way that appears both effortless and masterful. The key to this exhibition is to look from the monotypes to the sculptures and vice versa. The aesthetic gambits that King tries out on paper are echoed in painted metal. He seems no more willing to accept a distinction between two and three dimensions than between abstraction and figuration – or between riotous youth and sedate old age.

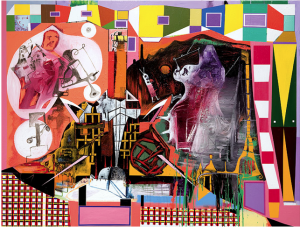

One of the strongest impressions one takes away from King’s sculptures and monotypes is that he has thoroughly enjoyed himself in the studio. I’m not sure the same could be said about Gareth Sansom’s new paintings at Roslyn Oxley9. Having recently turned 70, Sansom seems unsure as to whether this is a cause for celebration or a catastrophe. His solution has been to pursue his own idiosyncratic hybrid of biomorphic and geometric abstraction; cartoons that would be right at home in a San Francisco comic book; and odd, disjointed fragments of collage.

Does it work? The only possible answer is “yes and no”. There is a mad, infectious energy in these pictures, but they are so interiorised that we would have to peer into Sansom’s turbulent subconscious to ever know what’s going on. No artist strives so hard to be different, not simply from his peers, but from the entire human race. There’s something to recommend in this approach. Who wants to be like everybody else? But militant non-conformism also threatens to become its own form of mannerism.

The fragments of collage may be the least successful elements in these works, being reminiscent of some of Brett Whiteley’s late affectations. The painting is another matter – showing a flair for bold, in-your-face colour, and an imagination that seethes and bubbles like a witch’s cauldron. Words such as beauty and ugliness are completely meaningless in this context. Sansom’s paintings are like living organisms that threaten to slide off the canvas and creep across the gallery floor in search of prey.

A picture such as Fearless alien art school killers may contain a veiled critique of today’s art education, but there are no precise messages in Sansom’s paintings. There is probably more useful information in his titles, which are works of art in their own right. We are in the presence of a connoisseur of chaos who would have us believe there’s a master plan behind every brushstroke. That may well be true, but it’s hard not to feel that the line between ‘art’ and ‘pathology’ has become almost impossible to discern. Sansom would be in his element designing a production of The Nose.

William Kentridge: The Nose, Annandale Galleries, July 07 – August, 2010

Phillip King: Sculpture and works on paper, Defiance Gallery, until 7 August, 2010

Gareth Sansom: New paintings 2010, Roslyn Oxley9, July 15 – August 07, 2010

Published in the Sydney Morning Herald, July 31, 2010