Lawrence Daws had an “early” retrospective at the Art Gallery of South Australia in 1966, when he was thirty-nine years old. This seems remarkable when one learns that Daws, who born in Adelaide, had his first solo exhibition in 1954. Was he considered such a prodigy that twelve years’ work was enough for a show in one of Australia’s major art museums?

It is just as puzzling that Daws had to wait until 2000 before he was given another survey, this time at the Brisbane City Gallery, concentrating on the thirty years he had spent in Queensland. Ten years later he is the subject of a third retrospective, at the Caloundra Regional Art Gallery on the Sunshine Coast. The Promised Land: The Art of Lawrence Daws will be touring to nine other venues in Queensland and New South Wales over the next year, arriving at Sydney’s S.H.Ervin Gallery in June 2011.

While museum attention has been sporadic, Daws has held regular solo exhibitions and been included in numerous group shows. It is almost as though the art institutions have never been able to decide if he is important or insignificant. He has been adored and ignored, feted and forgotten in equal measure.

His is not a special case. Australia’s major public galleries have become notoriously reluctant to hold retrospective exhibitions for senior artists. The reasons are obvious: such shows are labour-intensive and costly, and – in all but a handful of cases – will not act as drawcards for paying audiences. To qualify for a retrospective at a state gallery nowadays an artist has to be dead, or trendy enough to pass muster with the contemporary art clones.

The Art Gallery of NSW is probably less culpable than other institutions, having recently surveyed aspects of the work of Jan Senbergs, Kevin Connor and Tim Johnson, but there is still a long way to go. It has increasingly fallen to the regional galleries to undertake retrospectives for artists who live locally. This is a positive development, testifying to the increasing professionalism of the regions, but it tends to let the big institutions off the hook, relegating major artists to smaller venues and more limited shows.

It was disappointing, for instance, that an artist such as John Coburn was given a retrospective at the S.H.Ervin rather than the AGNSW, and the same could be said about many others. Lawrence Daws is a case in point, as he has enjoyed a long and distinguished career that deserves a comprehensive overview.

The Promised Land, put together by the independent curators, Bettina and Desmond MacAulay, is a compact exhibition of some sixty items. Within these limits, largely determined by the capacity of the Caloundra gallery and other venues, the selection is as broad ranging as possible. The show begins with a small tonalist self-portrait from 1951, and ends with the stark landscapes and allegorical paintings of 2005-06. The journey between these points is a magical mystery tour, revealing an artist who is torn between a love of tradition and the urge to keep experimenting.

The experimental impulse translates into the fractured planes of a painting such as Crucifixion (1955), a dark, abstracted figure study that captures the dominant mood and style of that era. In The Dark Rider (1966), the canvas is divided into four rows of small hieroglyphs – a treasure trove of arcane symbolism for the Age of Aquarius. Then there are the technical experiments with collage and digital printing which find their way into large-scale paintings.

Alongside these works there are skilful, naturalistic drawings, lyrical landscapes, and small studies that show how Daws has never abandoned the habit of close observation. While many of his pictures are remarkably ‘straight’, others are so bizarre and cryptic that the imagery seems to have been dredged up from some dark corner of the subconscious.

The overall impression is ambiguous. One can admire the artist’s constant willingness to explore new horizons, but there is also the danger that his work is neither-one-thing-nor-the other. In other words, Daws’s work may be too conventional for some tastes, and too unusual for others. This might help explain his patchy relationship with the art museums. Although he may be seen as a younger contemporary of artists such as Arthur Boyd and Sidney Nolan, he is not a painter of Australian icons. Although he shares many affinities with Brett Whiteley, who was twelve years his junior, he is far less spontaneous in his approach.

Although Daws has an adventurous streak, one suspects that he has made a thorough study of those sources and influences that found their way into Whiteley’s work through a form of osmosis. Look at the way Whiteley expressed his admiration of Piero della Francesca in that monstrous pastiche called Fidgeting with Infinity (1966). Piero’s Baptism was blended with photographs of dead bodies in India, a bulging set of breasts, an endless highway, a blank thought bubble, and much else. The experience of Piero became a head trip that led to a variety of random, subjective associations.

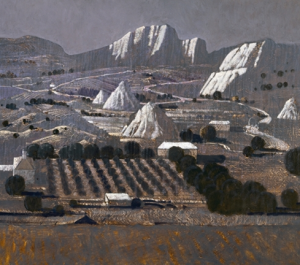

Daws’s love of Piero began with an examination of the mathematical underpinnings of his work. He was fascinated by the way Piero made use of perspective lines and grids. This intersected with Daws’s early studies in engineering and architecture, and would exert a lasting influence on his attitude to composition. He was also drawn to the small, precise landscapes that Piero included in paintings such as The Nativity (1470-75). Many of Daws’s later views of the Glasshouse Mountains contain visual echoes of those rolling Tuscan hills.

I only realised how deeply methodical Daws is, when I visited his studio several years ago, and saw how he had made the computer an integral part of his working process. Since the late 1980s he has been putting images on screen, planning and gridding up compositions as he would in a sketchbook. When the on-screen picture is complete Daws will copy it onto a canvas using the comfortably old-fashioned methods characteristic of all easel painters.

This orderly approach to composition is offset by Daws’s reading habits. The MacAulays provide a list that starts with Jung, Kant, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Herman Hesse, and goes on to include subjects such as alchemy, mandalas, the Tarot, the Bible, and paleogeography. All of this finds its way into the paintings, sometimes in the most bewildering combinations. Daws admits that he will often become obsessed with a particular image without being able to say where it comes from. He will use the motif over and again, trying to understand its deeper significance.

The results of this psychic product-testing can be quite extraordinary, as landscapes are overlaid with jarring imagery such as a bright red cage that stands out like a beacon against a low-toned backdrop. In Owl Creek III (1980), the red cage becomes an elaborate, empty bird house, suspended from a balcony looking out over the Glasshouse Mountains.

The largest and most complex painting in this show is Cain and the promised land II (1983) – a two-panel view of a sweeping, desolate plain framed by a set of imposing mountains. On the right-hand panel there are teeming crowds and monumental architectural features. On the left one finds a colony of small red cages, a vast egg, and a photographic image of a Peruvian vampire bat that projects a green laser beam from its eyes – not something one sees every day of the week.

Above this apocalyptic scene, six eyeballs go floating through the sky, emitting faint vapour trails. In a video that accompanies the show, Daws makes a brave attempt to explain this amazing concatenation of images, but it is clear that he is hardly less puzzled than his audience. The idea for the painting may originate in episodes from the Old Testament and a memory of riots in India, but there is no real explanation for the vampire bat or the flying eyeballs. The bat “looked evil”, and the eyes are perhaps those of an extra-terrestrial race looking down upon human folly.

One can hardly imagine a more dramatic example of an artist being led into uncharted waters by his own vivid imagination. When that artist is as sober, rational and intellectual as Lawrence Daws, it suggests that Socrates was on the right track when he said artists and poets were possessed of a divine madness. The philosopher had his “daemonic sign”, and so too does Daws. He may feel completely at home in the Queensland landscape, but he is still attracted to those things that cannot be seen except with the eye of the mind.

The Promised Land: The Art of Lawrence Daws, Caloundra Regional Gallery, April 30-June 27, 2010

Published in the Sydney Morning Herald February 20, 2010